Perforated eardrum and eardrum repair

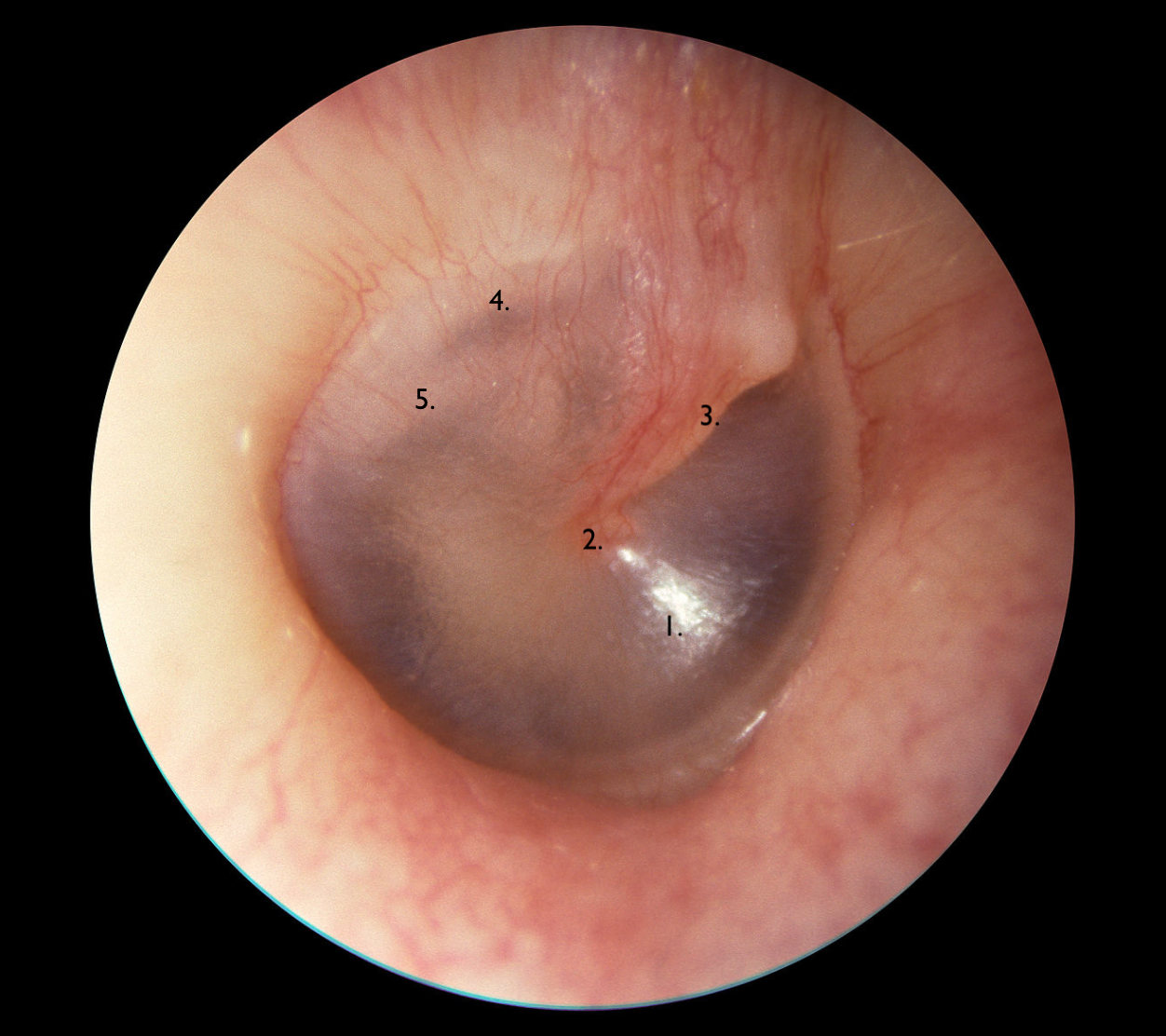

A healthy right eardrum (Michael Hawke, MD).

1. Pars tensa, the main part of the eardrum 2. Umbo: the centre of the eardrum 3. The malleus- one of the middle ear ossicles 4. The chorda tympani, a nerve branch which supplies taste to the tongue 5. Facial nerve in the middle ear.

What is the eardrum (tympanic membrane)?

The ear drum (or tympanic membrane) forms a barrier of skin and soft tissue between the external part of the ear and the delicate middle ear. This acts like the skin of a drum: it keeps out water and other debris, to protect the ear, but also acts as a very efficient way of conducting sound through to the three little bones in the middle ear (the ossicles) which serve to maximise the amount of sound which reaches the hearing organ of the inner ear.

The whole eardrum measures about 1.2 cm x 1 cm, and it moves only a few nanometres in and out during normal hearing. In fact, if the eardrum was the size of the whole of England, it would move in and out only a couple of feet. This demonstrates how amazingly sensitive our ears and hearing are.

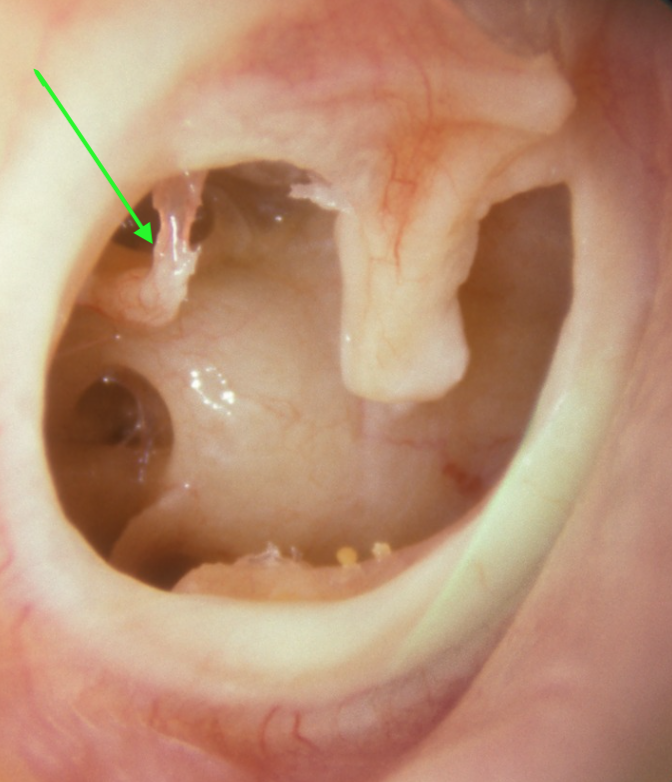

A large perforation of the right tympanic membrane (Michael Hawke, MD): the ossicles (small bones) of the middle ear can be seen through the hole, with some erosion of the incus (green arrow). The edges of the hole are scarred over: the hole will not close on its own.

What is a perforated eardrum and what problems can this cause?

Problems can arise when there is a hole in the eardrum, otherwise known as a perforation. The hole will allow water and debris to enter the middle ear, which can cause inflammation, infection and smelly discharge. Additionally, during colds, the lining of the middle ear can make quite a lot of mucus, which can then come out through the hole and become colonised with bacteria. In addition to the risk of ear infections, a hole in the eardrum will affect the efficiency of the eardrum in terms of transmitting sound through to the middle ear from outside. Generally speaking, the larger the hole, the more effect this will have on the hearing. Additionally, patients who have had ear infections may also have some mucus membrane adhesions and scarring in the middle ear, which can affect the vibrations of the ossicles, further reducing the hearing. Small numbers of patients may also have erosion of the ossicles as a result of previous infections, and so all of these factors have to be taken into account when assessing patients with eardrum perforations.

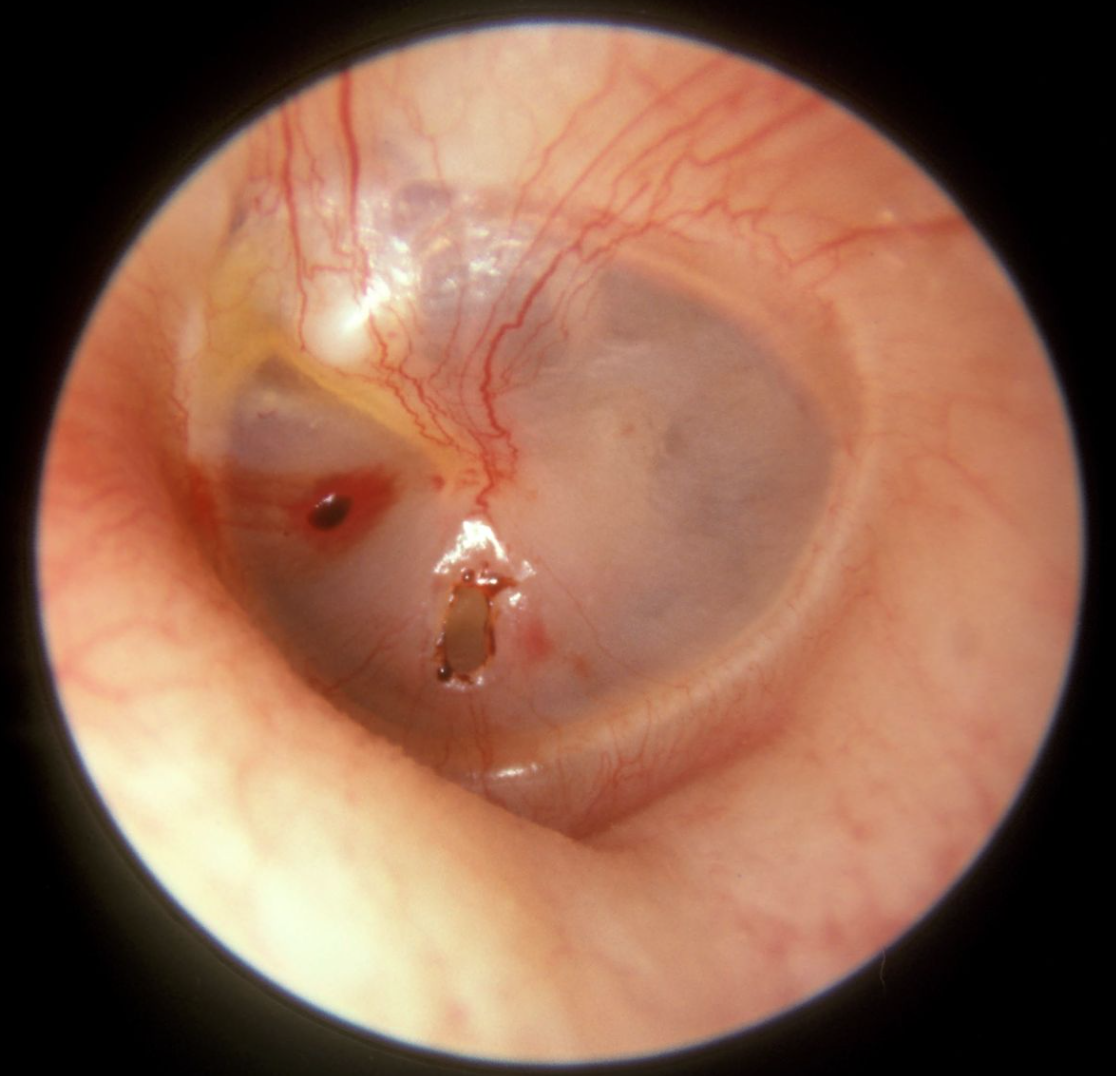

A perforation of the eardrum can occur after an ear infection, often early in childhood, but sometimes later in life. Alternatively, an injury to the ear (such as a slap across the ear) can cause a perforation. Sometimes, after previous ear surgery, including insertion of grommets, a small hole may be left in the eardrum.

A small perforation of the left eardrum after a slap across the ear (Michael Hawke, MD). This is likely to heal up on its own within 2-3 weeks, as long as the ear is kept dry.

Often, a perforation will heal up on its own. If a perforation develops, we generally advise keeping the ear as dry as possible, and the healing process may be improved by using gentle antibiotic drops such as ciprofloxacin, particularly if the ear has been infected. Generally, the hole will heal up within 2 to 3 weeks, so it is particularly important to keep the ear dry during this period and to avoid pressure changes: swimming and flying should be avoided for about six weeks afterwards, to make sure that everything has healed.

If the perforation has been present for quite a long time, it is more likely that the edges of this will scar over, meaning that the skin can’t grow back across the hole to seal it. In these cases, it is unlikely that the perforation will close on its own, and so we may then consider an operation to repair it. This is called a myringoplasty or tympanoplasty. This has the aim of closing the perforation so that the eardrum is intact again, protecting the middle ear from water and debris, so reducing the risks of further infections. Additionally, there may be a possibility of improving the hearing by making the eardrum more efficient, although this is not guaranteed, as the hearing may be affected by other factors, as described above.

What might happen if a tympanic membrane perforation is left unrepaired?

The eardrum normally forms an intact barrier to protect the middle ear structures. A hole in the eardrum is like having a window open in a car: it is certainly possible to make many journeys with a car window open without any problems. However, if one is unlucky, water and dirt may be splashed through the open car window, causing damage to the contents. The same sort of thing may occur with a hole in the eardrum.

In many cases, patients may have minimal symptoms, particularly if the affected ear is kept dry. However, this is often difficult to achieve, particularly in children, and especially with certain activities such as swimming. Entry of water and soap into the middle ear can cause inflammation, infections and smelly discharge. With each of these ear infections, the delicate structures in the middle ear can be damaged, possibly resulting in hearing loss and other complications. It therefore makes sense to consider repairing and eardrum perforation, rather than simply leaving it open, although the decision depends on individual circumstances, particularly the frequency and severity of ear infections.

When is the best time to repair an eardrum perforation?

This has been the subject of a lot of debate among ENT surgeons. On the one hand, it is ideal to try to repair perforations relatively early in life, to reduce the risks of further ear infections, and to allow resumption of normal activities, such as swimming. On the other hand, if we repair perforations too early, for example in very young children, they have a high chance of having further colds and ear infections, which may result in more ear infections and re-perforation. Therefore, many ENT surgeons will tend to delay repair of a perforation until children are at late primary school age (9-10 years old), where the risks of further ear infections are less. However, there may be circumstances where eardrum repair can be considered at an earlier age, for example in younger children with really problematic ear infections.

How is a perforated eardrum repaired?

A perforation of the eardrum can be repaired in a number of ways, according to the size of the hole and its location. In the UK, these procedures are almost always performed under general anaesthetic, using a high power operating microscope and sometimes endoscopes, and the surgery takes 1-2 hours or so.

These repairs involve roughening the edges of the perforation so that they are stickier and inclined to heal, with the addition of a graft, which acts as a scaffold for the skin to grow across.

With all of these methods, we have to strike a balance between successful repair of the perforation, improvement of hearing and ease of recovery.

Interlay repairs: plugging the hole

Very tiny holes (1mm or so) can be repaired very simply. The edges of the perforation are roughened with a probe to remove the healed edge, and a small piece of gelatin foam or fat can be placed over the hole, allowing it to heal underneath.

Small holes (2 to 4 mm in diameter) can be repaired using a small plug of cartilage which is taken from the tragus, the triangle of cartilage just in front of the ear canal. A small disc of cartilage is removed, and then the edge of the disc is cut very gently with a knife, to “butterfly” open the edge, like butterflying a prawn. This disc of cartilage is then plugged into the hole, allowing the eardrum to heal over this. This is illustrated here.

These two methods are known as interlay repairs, as the graft material is laid into the hole. They have the advantage of being very simple, causing minimum disruption to the eardrum and the middle ear, and generally allowing very fast recovery, with minimal amounts of dressings in the ear.

However, the grafts are not always easy to secure, and may become dislodged if the patient sneezes or blows their nose, for example, and the healing of the perforation is sometimes difficult to predict. Additionally, because the eardrum is not lifted up, the ossicles and other structures in the middle ear cannot be examined during the operation. Therefore, if patients have significant hearing problems before the operation, as a result of adhesions and scarring in the middle ear, these cannot be easily addressed during the surgery.

Underlay repairs: the eardrum is lifted up and the graft is placed underneath

As an alternative to these interlay methods, there is also the possibility of lifting up the eardrum during the operation and then placing a graft underneath the hole, laying the eardrum back down again on top of the graft. This is called an underlay myringoplasty or tympanoplasty. This can be likened to lifting up the pastry lid of a pie, allowing the contents to be examined, before the pastry lid is then replaced.

This has been a very standard way of repairing eardrums for many years, and generally allows successful repair in most cases, while at the same time enabling examination the middle ear structures, removing adhesions and scar tissue, particularly in those patients who have hearing reduction before the operation.

The grafts are also generally easier to secure with underlay methods, and therefore the chance of successful repair may be a little higher than with interlay methods, although of course this depends on other factors, including the size of the perforation and its location – a hole in some areas of the eardrum is more difficult to access than in others.

However, the underlay methods generally are associated with more prolonged healing time afterwards, and may involve an incision behind the ear or in front of the ear to allow easier access to the ear canal when performing the operation. For the graft, we generally use a little piece of muscle lining from one of the chewing muscles around the ear (like the thin membrane on the edge of a steak) or a small piece of cartilage from the ear itself.

This procedure is beautifully illustrated: please click here (under the tympanoplasty section)

What is the typical recovery after eardrum repair?

Recovery depends to some extent upon the method used.

The interlay methods are generally associated with the quickest recovery, and many patients can return to school or work within a few days. With the underlay methods, particularly if there has been an incision behind or in front of the ear, the recovery time can be a bit longer, and patients may require a week off normal activities.

I generally use dissolvable gelatin dressings in the ear canal and dissolvable stitches to close any incisions. I prescribe antibiotic drops to use for two weeks after the surgery in order to keep the dressings nice and moist, and any residues of the dressings can be removed in clinic, at around 2 to 3 weeks after the operation.

With all of these eardrum repairs, we would generally recommend a period of 6 to 8 weeks where the ear is kept dry, using cotton wool or a silicon plug, with complete avoidance of swimming and flying.

What are the benefits and risks of the surgery?

The main aim of eardrum perforation repair is to provide an intact eardrum, allowing swimming and other activities without further ear infections. The second aim is to improve hearing, although, for reasons discussed above, this is less easy to guarantee.

A perforation is usually successfully repaired in about 8 out of 10 patients or so. This success rate will vary according to the size and location of the perforation and some other factors, and there are slight differences between the methods, as described already. In a small number of patients, the perforation may not fully heal after the operation, or alternatively it may heal successfully but then break down months or years later.

The incisions used to access the ear canal (behind or in front of the ear) and to harvest cartilage or muscle lining for grafts, will generally heal very well. In small numbers of patients, there may be some wound infection, which is usually treated with antibiotics. With incisions behind the ear, the ear may stick out a little bit for a few months after the operation, gradually pulling back in as everything heals with time. Very occasionally, the incision may scar heavily, particularly in patients who have pigmented skin. This is known as a keloid scar. In patients where keloid scarring is likely, I tend to use small steroid injections at the end of the operation to reduce the risk of this happening.

Other problems can occasionally arise from the structures within the middle ear:

Any ear surgery can result in some dizziness and imbalance afterwards, and if this occurs, it is usually temporary rather than permanent.

Small numbers of patients may also complain of hearing a noise in the ear (tinnitus). Again, if this occurs, it is usually temporary, but can rarely be permanent.

Although the surgery will hopefully help to improve the hearing in the operated ear, there is a very small chance of hearing loss after the operation. This may be predicted, for example if one of the small ossicles in the middle ear is eroded and has to be removed to allow clearance of infection, but very rarely it may also occur from injury to the ossicles or the inner ear itself. However, I should stress that this is very unlikely. Although the structures are very small and delicate, the operation is performed using a microscope, so that there is excellent visualisation of the operated area.

A small taste nerve (the chorda tympani) runs under the top of the eardrum, and can be pulled and very occasionally injured when the eardrum is lifted up. This can result in altered taste on that side of the mouth, which can be persistent or even permanent.

The facial nerve, which moves the muscles on that side of the face, passes through the middle ear. This is usually surrounded by a bony coating, but occasionally in small numbers of patients, some of this bony coating is absent. With eardrum repairs, it is exceptionally unlikely that the nerve will be injured during the operation. However, sometimes when dressings are applied, they may be a little bit of compression of the nerve, resulting in some facial weakness on that side of the face. This is very uncommon during these sorts of operations, and is only very occasionally seen. In almost all cases, the weakness is temporary and will improve with time.

Overall, despite these small risks, repair of tympanic membrane perforations is straightforward and successful.